The Cartography of Devotion: Mashhad and the Architecture of Persian Pilgrimage

- 15 February 2026

- امیرحسین عباسی

The muezzin's call fractures the pre-dawn stillness, cascading across a city where faith has never been abstract—where eight centuries of footsteps have worn grooves into marble thresholds, and the act of prayer remains as infrastructural as water or light. Mashhad, Iran's second-largest metropolis, exists at the confluence of the sacred and the quotidian, a place where the rituals of devotion shape urban form as decisively as rivers shape valleys. To understand this northeastern Iranian city is to reckon with the peculiar alchemy that occurs when geography becomes theology, when a single eighth-century martyrdom transforms a Silk Road waystation into the spiritual lodestar for millions.

The Gravitational Pull of Sanctity

The Imam Reza shrine complex—covering nearly twenty million square feet of courtyards, iwans, and prayer halls—functions less as a monument than as a living organism, its boundaries expanding and contracting with the rhythms of the Islamic calendar. Each year, between twenty and thirty million pilgrims converge on this northeastern outpost, their journeys tracing routes that predate modern nation-states, following pathways established when Khorasan province represented the easternmost reach of Abbasid power. The shrine's gold-leafed dome, visible from nearly every vantage point in the city, serves as both beacon and anchor, organizing Mashhad's spatial logic around concentric circles of holiness that diminish gradually toward the periphery.

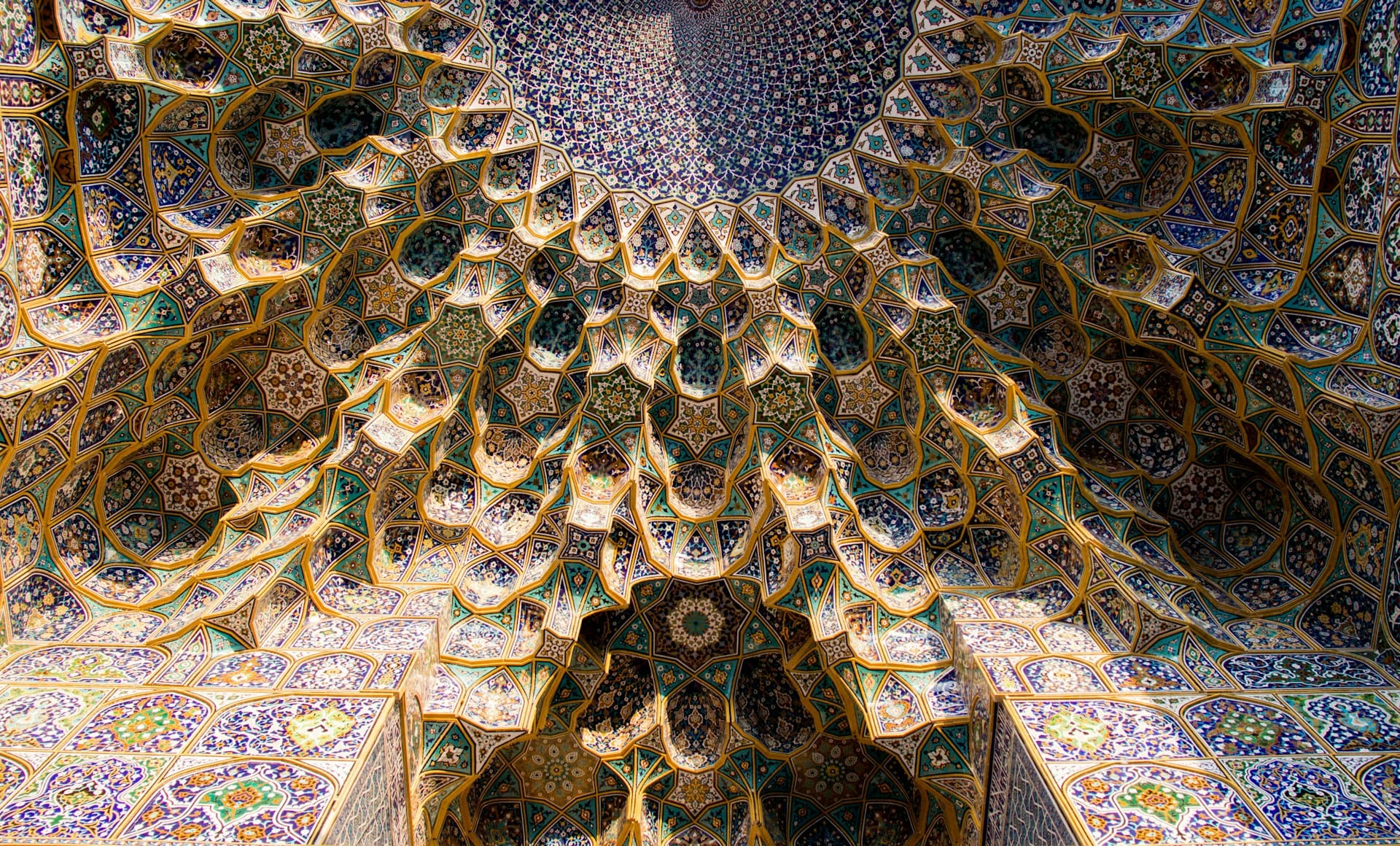

This gravitational model of urban development has produced a city of striking contrasts, where centuries-old madrasas abut shopping arcades selling prayer beads alongside consumer electronics, where the architectural vocabulary shifts from Timurid tile work to postmodern glass within a single city block. The shrine itself has accumulated layers of patronage like geological strata—Safavid modifications overlay Ilkhanid renovations, which in turn obscure earlier Seljuk foundations—creating a palimpsest where each dynasty's aesthetic ambitions remain partially legible beneath subsequent interventions. Walking the shrine's perimeter becomes an exercise in comparative chronology, a physical passage through the shifting expressions of Persian-Islamic statecraft across eight hundred years.

Yet Mashhad's significance extends beyond its function as pilgrimage destination. The city occupies a strategic position along historical trade routes connecting the Iranian plateau to Central Asia, a location that has made it perpetually vulnerable to conquest and perpetually valuable to empire-builders. The Mongol sack of 1220 nearly erased the settlement entirely; its resurrection around the shrine of the eighth Shia imam represents both religious devotion and calculated economic opportunism, as merchants and craftsmen recognized the commercial potential of servicing an endless stream of pilgrims. This dual character—simultaneously pious and pragmatic—has defined Mashhad's evolution, producing an economy structured around the logistics of faith, where hotels, restaurants, and carpet vendors exist in symbiotic relationship with devotional practice.

The Topography of Memory and Erasure

Contemporary Mashhad sprawls across the Kashafrud River valley, its population of 5.5 million making it the capital of Razavi Khorasan province and a critical node in Iran's northeastern corridor. The city's expansion has been both dramatic and problematic, consuming agricultural land at rates that alarm urban planners while struggling to accommodate population growth driven by rural-to-urban migration and the constant influx of pilgrims who decide to remain. The result is a metropolitan area where planning yields to improvisation, where informal settlements proliferate alongside government-sponsored apartment blocks, creating a built environment that reflects decades of economic volatility and geopolitical isolation.

The urban fabric reveals layers of contested history. The tomb of Nader Shah Afshar, the eighteenth-century military genius who briefly restored Persian imperial power, occupies a conspicuously modest position relative to the shrine, a spatial subordination that speaks to the uneasy relationship between secular authority and religious legitimacy in Iranian political culture. Similarly, the mausoleum of Ferdowsi—the tenth-century poet whose Shahnameh codified Persian cultural identity in epic verse—sits some distance from the city center in Tus, the ruins of his birthplace serving as pilgrimage site for a different kind of devotee, those who venerate linguistic heritage. These competing sacred geographies map the tensions between Arab-Islamic and pre-Islamic Persian identity, tensions that have animated Iranian cultural politics for a millennium.

For the visitor willing to look beyond the shrine's overwhelming presence, Mashhad offers evidence of Khorasan's long tenure as a crucible of Persian high culture. The region produced some of Islam's most influential theologians and Sufis, including Al-Ghazali and Attar of Nishapur, whose philosophical innovations reverberate through Islamic thought to the present. It was here that the synthesis of Zoroastrian cosmology, Greek philosophy, and Islamic revelation achieved its most sophisticated expressions, here that the Persian language reasserted itself as a vehicle for both mystical poetry and scientific discourse after centuries of Arabic dominance. Understanding Mashhad requires acknowledging this intellectual genealogy, recognizing the city as heir to traditions that long predate its current configuration.

Passages and Permanence

The challenge facing contemporary Mashhad involves reconciling its role as Iran's premier pilgrimage city with the demands of modern urbanization. Recent expansions of the shrine complex have required the demolition of historic neighborhoods, erasing centuries-old residential patterns in service of accommodating larger crowds and providing contemporary amenities. The tension between preservation and development plays out daily, as municipal authorities attempt to balance UNESCO-worthy architectural heritage against the practical requirements of hosting millions of visitors annually in a city where infrastructure perpetually lags behind need.

Yet perhaps this constant negotiation between past and present, between sacred obligation and urban necessity, constitutes Mashhad's most authentic characteristic. The city has never been static, never represented a museum-piece version of Islamic urbanism. Instead, it remains what it has always been: a place where faith generates commerce, where theology shapes geography, where the eighth-century murder of a prince continues to organize the lives of millions. In an era of calculated authenticity and curated heritage experiences, Mashhad offers something increasingly rare—a living religious landscape where devotion still dictates daily rhythms, where the spiritual remains stubbornly material, embedded in stone and gold and the worn surfaces of countless prostrations.